It has stopped raining olives here at Quinta do Tedo, which means it’s time for our annual Harvest Show and Tell, starting with a deep dive into the unique history and culture of Douro Valley’s oliviculture.

The europea olive tree species that we harvest is the only species of the Olea genus to produce edible material. Horticulturalists have selectively bred Olea europea’s 139 true varieties into over 600 different cultivars with nuanced aromas, flavours and textures, depending on the final product they are destined for (olive oil, olives in brine, dried olives, olive paste, etc.)

While the first records of human-cultivated olive trees date back to 5,000 BC in Iran, Syria and Palestine, oliviculture spread with the Roman Empire across the hot and dry Mediterranean basin and Portugal, where drought-, fire-, and decay-resistant olive trees thrived.

Post-Roman oliviculture in Portugal advanced from the 8th century onwards under the Moors, whose word for “olive juice”, “al-zeit”, eventually morphed into “azeite”, the modern Portuguese word for olive oil. This “liquid gold”, which was not easy to produce nor cheap to consume, was cherished and traded as a source of nutrition (today, Portuguese consume an average 8 litres per person each year) and, eventually, also medicine and fuel for lighting in the mid-16th century. Olive oil became an integral part of the Mediterranean economy and diet.

Olive trees were planted in Douro Valley, along man-made, stone-wall terraces to replace vineyards destroyed by phylloxera in the late 19th century, and in Southern Portugal to support the sardine canning industry that boomed since the 1900s. Today, the Tràs-os-Montes e Alto Douro Protected Designation of Origin (DOP) has the most centenary olive trees (although the oldest resides in Central Portugal and still bears fruit at 3,350 years old!), while the Alentejo is the DOP is the largest producer of olive oil in the country.

For some time, Portuguese olive oil hid in the shadows of Spanish and Italian olive oil. Spain and Italy purchased Portugal’s cheaper, and perhaps higher quality, olive oil to label and sell across the world as their own. Furthermore, the Portuguese olive oil industry took a blow to margarine, introduced in the 1960s as a cheaper and allegedly healthier fat. Production nose-dived through until Portugal joined the EU in 1986, at which point the government was offering farmers subsidies to destroy what seemed like the unprofitable olive groves throughout the country.

A decade later, while olive oil’s importance as a “healthy food” and even a luxury good grew in the international market, Portuguese government officials and businessmen started to invest in what was more profitable, rather than what was more subsidized. Portuguese olive oil production was revived as a quality product of cultural importance, largely thanks to the establishment of 6 olive oil DOPs and an increase in rural and agricultural tourism, use of olive oil in haute-cuisine, and competitions like the International Olive Oil Competition in New York from which Portugal brought home 17 Gold Medals in 2020! Since 2016, Portugal has been the world’s 8th largest quality olive oil producer.

Quinta do Tedo’s 800 trees between 50-120 years old are organically farmed, thus neither irrigated nor treated with fertilizers or pesticides. Our groves include the cordovil, verdial, carrasquenha, moleirinha, and a dozen others varieties which, similar to the 25+ grape varieties growing in our organic vineyards, we blend to achieve more complexity and balance in the final product, be it our olive oil, or Douro DOC wines, or Ports.

In Douro Valley, olive trees were historically planted at the edge of vineyards to mark land ownership boundaries and to signal the arrival of disease to farmers so they could take precautionary measures in their more lucrative vineyards. Olive trees also increase the biodiversity of our 18-hectare estate and Tedo River eco-reserve. Wild asparagi grow under our groves in Spring, while blue tits, field owls and the common swift nest or feed in their branches throughout the year.

We prune our olive trees like doughnuts, opening a hole in the middle of the canopy to increase sun exposure for even ripening and to promote the ring of branches’ outward growth so we can more easily harvest them. In April, flower blossoms bud from “armpits” connecting leaf stems to their branches. Come May, the flowers self-pollinate and, within a matter of weeks, only 2% of those fertilized flowers grow into fruit, 40% of which the olive trees drop during ripening, so as to nurture only the most promising olives to full maturity.

This natural loss is necessary for the olive tree to produce quality fruit and withstand the fruit’s weight of up to 50 kilos per tree, when grown conventionally. Our low density, organic olive groves produce even less fruit, around 20 kilos per tree, as they grow under the pressure of Douro Valley’s dry, hot climate and infertile schist soil, without irrigation. We also harvest them earlier, to maintain low acidity and an iconic piquantness in the final flavour of the 5-6 litres of Extra Virgin Olive Oil we squeeze out of each tree.

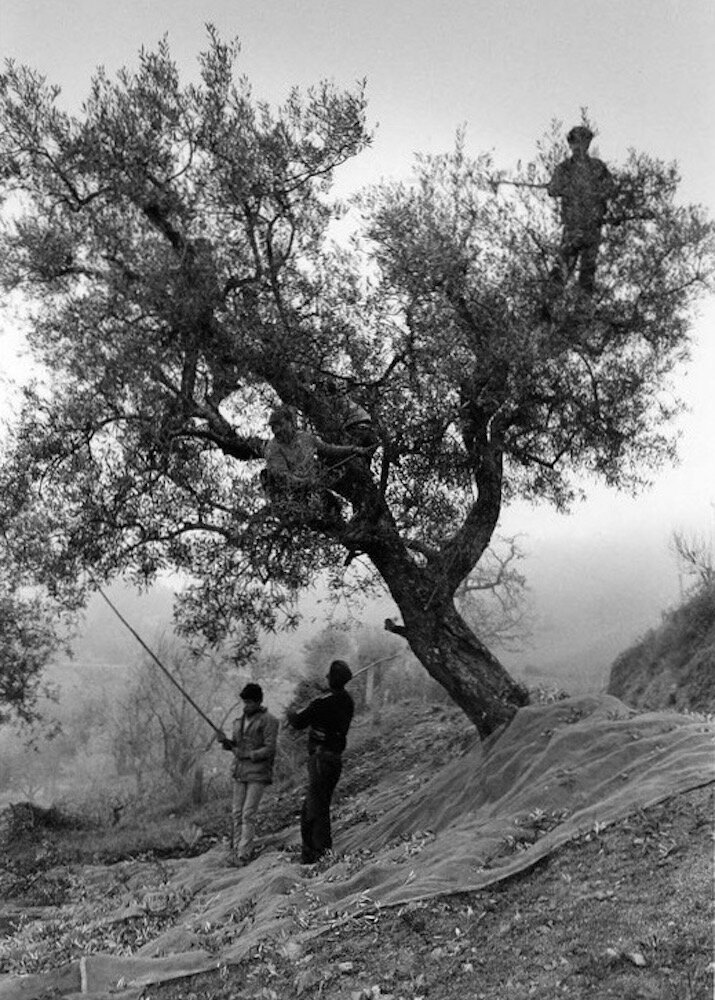

“Move those sticks, olive shakers,

Pick up fast, olive pickers,

Pick up those golden beads,

Falling from olive trees.”

This old harvest-time chant still accurately depicts the phenomena of our team climbing and hitting the olive trees with long, strong sticks until all the fruit falls into nets arranged around the tree’s base and propped up at the ends to ensure no “golden beads” are lost down the steep slopes into the Tedo River. We sort out the leaves and damaged fruit by hand and pour the olives into crates which take a stong back and steady foot to hike up or down terraces to our truck which ushers them, at the end of every day, to Agrifiba, an organic press 30 minutes away in Vila Real.

Decades ago, olives were harvested much later, as a Christmas family tradition, and were stored in bins of water until pressing after New Years. Agrifiba’s technician, João Fernandes, refers to this as sacrilege. Find out why in January 2021’s Behind the Scenes of our Extra Virgin Olive Oil: Part 2, when we’ll discuss the pressing, tasting, and best use of our “liquid gold” which you can find in the EU through our e-shop or in the US through Rachel Farah Selections. Enjoy!

written & photographed by Odile Bouchard, 1980s black & white photos by Georges Dussaud