In 2020, we challenged our certified-organic estate grapes and winemaking team to make a delicate, dry and terroir-driven Douro DOC Rosé? Do you remember how perfectly it satisfied those summer cravings for something light and fresh? Do you remember that it sold out in July, so soon after it launched in February 2021, leaving us rosé-less for the rest of summer?

As of early April, our Douro DOC Rosé is back in our tasting room, online shop, Bistro Terrace and B&B minibars - this 2021 edition is tasting brighter than ever and (fingers crossed!) it won’t run out so soon!

Similar to our 2020 edition, we fermented and aged Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca and Tinta Roriz (the iconic grape trio at the base of our red Douro DOC wine and Port blends) for 5 months in part-stainless steel part-cocciopesto amphora. The resulting rosé is precise and mineral, soft and pure, complex and food-friendly. Its extremely pale color is the result of very little contact between the grapes’ juices and skins and its delicate red fruit and floral character beautifully sings to Douro’s native red grape varieties within.

In a world of endless shades, flavors and purposes of rosé, we’re proud to say ours is as serious as it is trendy. Let’s take a moment to explain that distinction and dive deep into the surprisingly ancient and versatile history of rosé. Read on!

Many believe the rosé revolution started in France after the 1990s with an elegant provençal-style that has today become many winemakers’ “true North”. However, cultivated ancient Greek winoes actually preferred light, pale, watered-down field blends of red and white grapes because they were more approachable. Harsh and tannic “pure wines” were for barbarians.

Once Greek traders brought vines to Massalia (aka Marseille) in 600 BC, Southern France became the coveted Medieval epicenter of the best rosés that were enjoyed in Rome and across the Mediterranean through Roman trade-networks. Making a delightful rosé was a lot simpler back then than making a crisp white or rich red wine. The first pure red wines were nearly undrinkable but, with time, the Greeks and Romans learned how to vinify red and white grapes into as delicious of expressions apart as together. Nevertheless, rosé wines were cherished for centuries and continue to evolve into both the best and worst expressions of the trendy rosés we drink “yes-way”, “all-day”, today.

A darker, violet-colored rosé or “claret” kickstarted Bordeaux’s wine culture and became popular amongst the English between the 1700s and late 1900s. Then, the 19th- and 20th-century tourism boom in Southern France’s Côte d’Azur allured elites, eager to quench their thirst with something fresh and pretty with, say, a chilled glass of pale rosé? Rosé quickly became the poster child for luxury, glamor and summer vibes and attracted new consumers - women and youth. In the first decade of the 21st century, rosé production increased by 31% in France where consumption has nearly tripled since 1990. France (and the tourists that la vie en rose attracts) is today’s largest rosé consumer, followed by the US.

But that’s hardly the whole story! We can’t talk about rosé without mentioning another player with perhaps an even more influential, but also abusive, role than France in the rosé craze - Portugal!

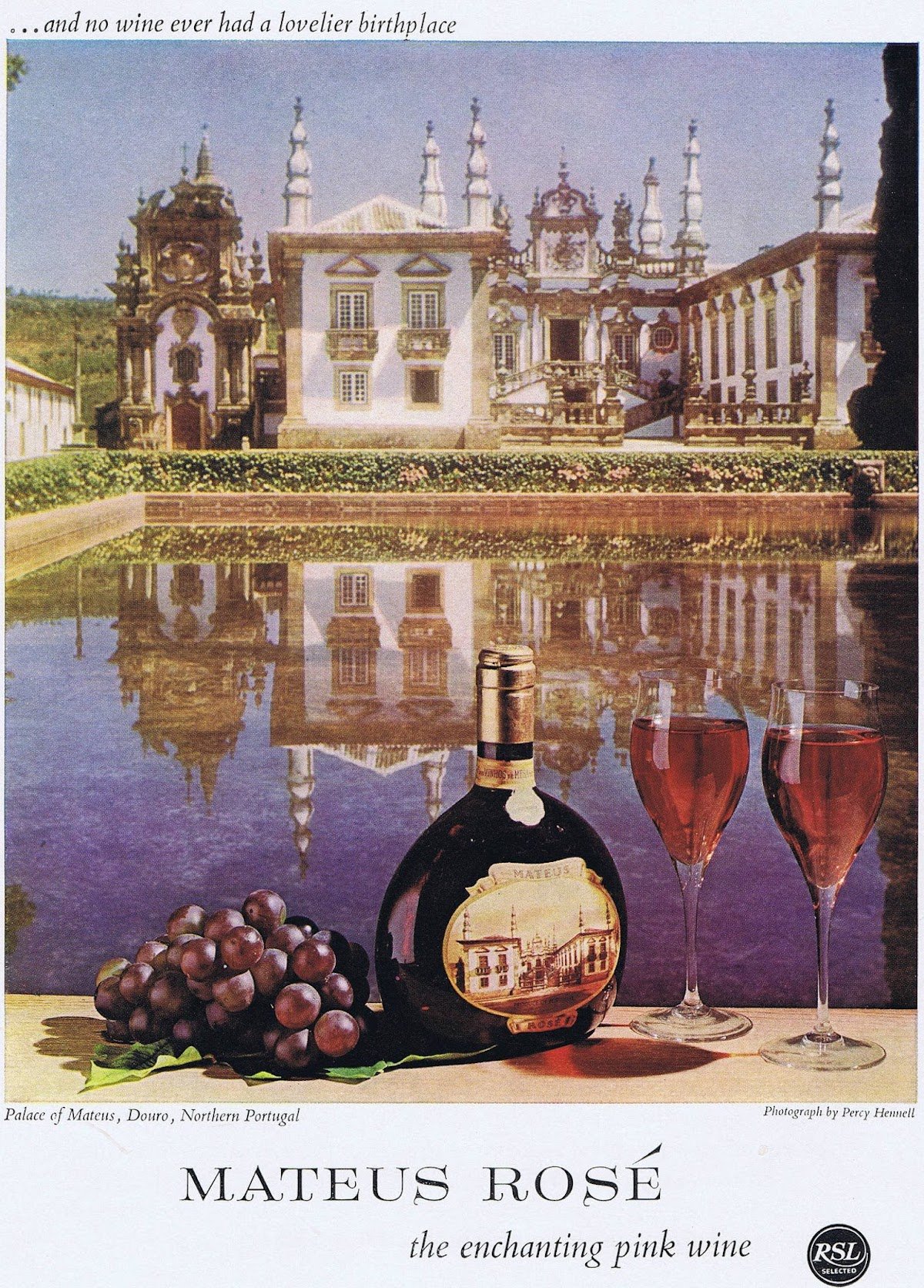

In 1942, Sogrape - the largest producer and distributor of Portuguese wine - launched Mateus Rosé - the most well-known rosé brand in the world today. Sogrape’s founder, Fernando van Zeller Guedes, designed Mateus Rosé and its iconic WW2-flask-resembling-bottle for the Brazilian market hoping sales could counter the decline in Port wine consumption during the WW2. Little did van Zeller or anyone expect Mateus Rosé to become an overnight success and post-war phenomenon!

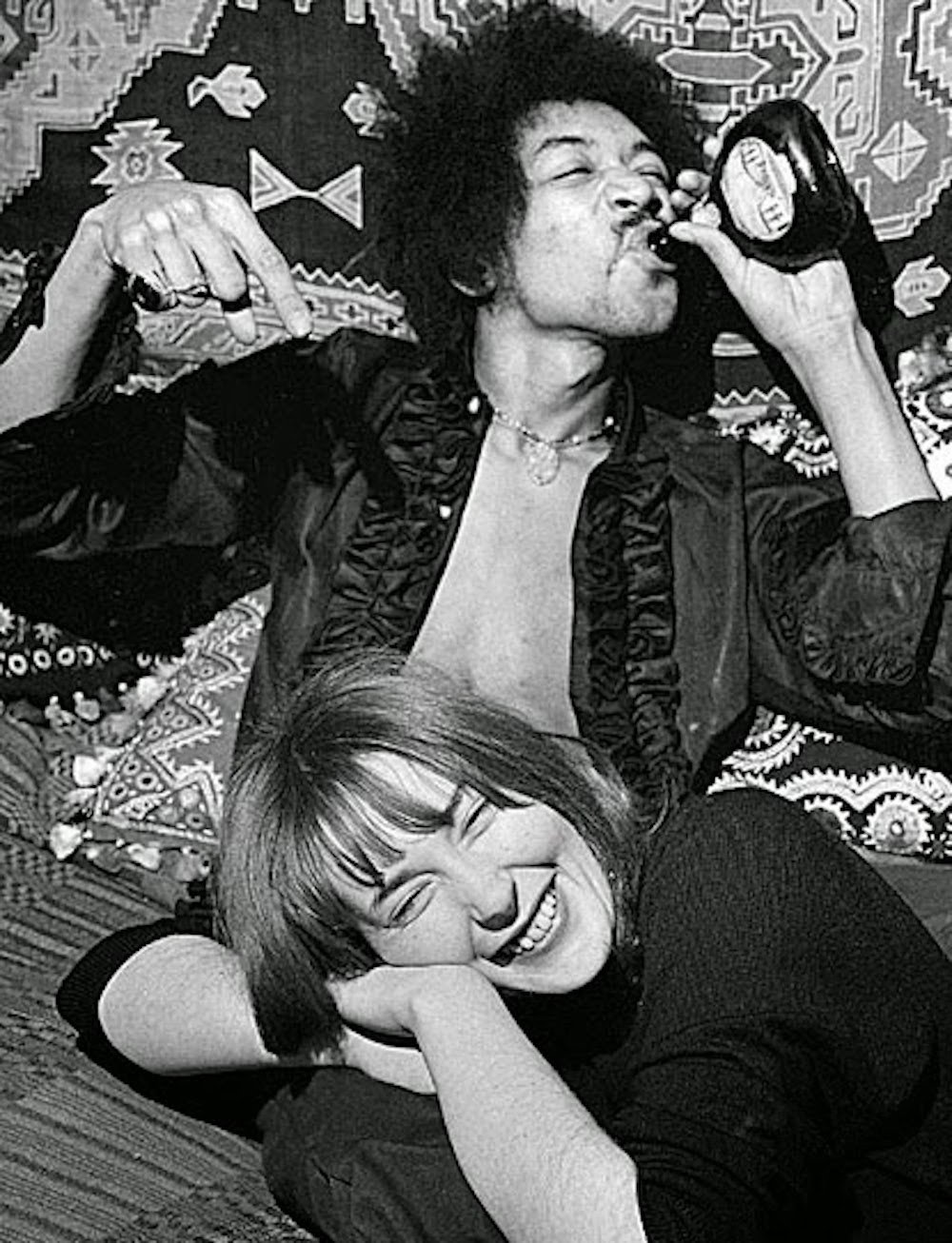

After WW2, an overwhelming demand for Mateus Rosé quickly spread across the world, catching on in the UK, Portugal’s long-established ally, and new markets like the US, Hong-Kong, Japan and Australia. In 1977, America’s Frontier Airline served Mateus Rosé during their meal service. Mateus Rosé fueled the US Army through the Cold War. Vintage photos of Mateus Rosé in the hands of Jimi Hendrix and Steve Jobs percolate the internet. Mateus Rosé was supposedly among Queen Elizabeth II’s (and Saddam Hussein’s…) favorites wines. An iconic line in Elton John’s 1973 hit, Social Disease, goes "I get juiced on Mateus and just hang loose.”

By the 1980s, over 3 million cases of Mateus Rosé were sold annually worldwide, making up 40% of Portugal’s entire wine exports then. Fast forward to today, over 20 million bottles of the iconic, medium-sweet, slightly-fizzy and dirt cheap Mateus Rosé are sold each year in over 120 countries.

Italy and Spain were quick to piggyback on the rosé trend that France and Portugal set the stage and created demand for. Rosé is now made in every wine-producing country - even the English make high-quality rosé in Kent and Decanter and other international wine challenges are finally taking the rosé category seriously. In 2008, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie purchased Chateau Miraval in Côtes de Provence to make expensive rosé - a “nectar for the stars”.

Modern rosés range from sweet and sparkling to still and dry. They can be the color of partridge eye (a Middle Age descriptor coined in Champagne that refers to the pale pink color of this bird struggling in death’s grip) or the fuchsia of cranberry juice. Rosé is served as an easy vin de soif (“wine to quench thirst”) or complex and gastronomic pairing for seafood, grilled chicken, fresh cheese, bright salads, light pastas, exotic Thai and Middle-Eastern dishes.

Nary a good success story comes without struggle. Sogrape planted entire vineyards just to rosé-adept varieties like Baga, Rufete, Tinta Barroca and Touriga Franca to hone an increasingly better rosé whose appeal might even surprise you, if tasted blind, as it has many a sommelier. But other brands like Portugal’s Lancers and California’s Sutter Home White Zinfandel produced sweet, cheap and bulk “blush wines” to satisfy growing demand for rosé. These tarnished rosé’s reputation along with the prospects of anyone trying to make and sell good rosé.

Fine wine and rosé drinking culture grew miles apart into the 1990s - nobody wanted “Lancers poisoning” or a “Mateus hangover”. Wine merchants like Kermit Lynch criticized these low-quality rosés for devaluing the existence of true, high-quality rosés. Sommeliers never served rosé and consumers never asked for it.

It wasn’t until the early 2000s that rosés were resurrected under respectable projects like Domaine Dujac and de la Romanée Conti that embraced the challenge to make great rosé with the right grapes in the right regions, not as a second-thought use of bad grapes they didn’t want to spoil their finer wines. By the summer of 2014, most New York bars and restaurants served fantastically complex and gastronomic rosés by the glass. This rebooted rosé’s trendiness and innovation, which you can learn all about if you visit the Pink Palace in the World of Wine museum complex next time you're in Porto!

If you head from Porto to Douro, check out Vila Real’s beautiful, baroque Mateus estate on the way. Sogrape’s Fernando van Zeller Guedes bought grapes from here to produce his legendary rosé and offered the owners royalties on each bottle sold with their mansion’s image on the label (inspired by revered Bordeaux’s Château-adorned labels). Thinking the product would see little success, they opted for a downpayment worth hay-pennies in comparison to the billions of euros and millions of bottles Mateus Rosé amounts to today, 80 years later.

Team Tedo celebrates the launch of our Douro DOC Rosé!